2025: A year of recalibration, resiliance and real talk

TL;DR: This year taught me that producers want conversation over courses, that taste can't be automated, that presentation matters more than ever, and that real DEI work requires action not just anger. I learned to price my expertise properly, got comfortable on LinkedIn, helped get Kelly Gordon to Cannes, and distilled everything I know about CVs and producer career positioning into a guide. The industry is struggling at every level, but empathy and genuine partnership still win. I'm still slow compared to other recruiters, still thorough, and better value pound for pound than anyone else doing what I do.

January: The Power Hour Validation

The year opened with an immediate signal that something was shifting. From the moment I came back from christmas, my inbox tripled with producers reaching out compared to the previous year. Not just for job leads—they wanted conversations. Market insights. Reflections on where the industry was headed. Advice and support. It felt like the entire production community had collectively decided that 2025 was the year to get serious about their careers.

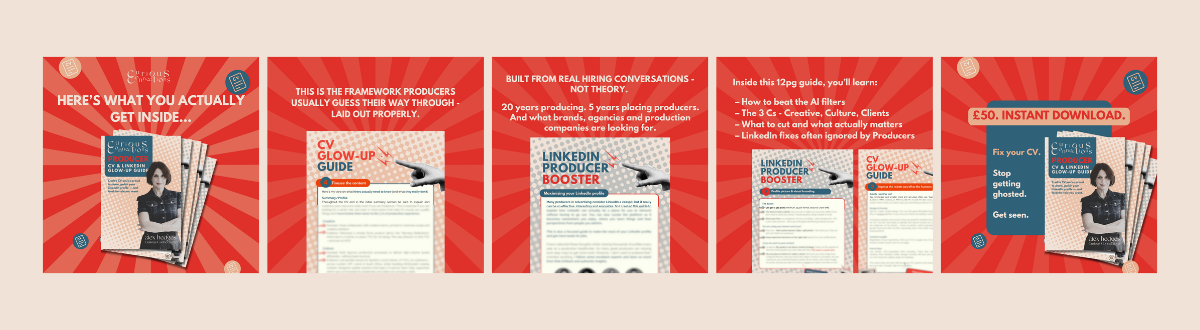

This surge coincided perfectly with the soft launch of my Power Hour sessions. I'd structured two offerings: a self-paced "Glow Up" guide at a low price point, and one-to-one sessions at £99—deliberately priced low to test the waters. That testing period taught me more about what producers actually need than any amount of market research could have.

Hardly anyone bought the self-paced option on its own. ( BTW I think that guide is brilliant, it holds your hand to make your CV pack a punch, but to sound like you.) But it was the 1:1 power hours that sold out immediately. Every single time I posted about them, I'd get bookings. The message was clear: producers want conversation. They want someone who understands the nuances of their specific situation, who can see the patterns of how production is evolving from a unique vantage point, who will give them honest feedback about their CV, their LinkedIn and their next move.

I loved delivering these sessions. The follow-up calls, the email check-ins, watching people implement advice and land roles—this work that energises me and reminds me that I’m in the right game. But it was a lesson I had to spend months working through: when you deliver real value, you need to charge accordingly. I care deeply about the producers I talk to—I understand money is genuinely an issue, especially with redundancies hitting every corner of the industry, and I want to make this support accessible. But it has to work both ways. At £99, the hours I was spending on follow-ups, detailed feedback, and ongoing check-ins simply weren't sustainable, no matter how much I believed in the impact.

So by the end of this year, after delivering over 20 Power Hours, it clicked. I was hearing the same concerns in each power hour: how to structure a CV that gets past ATS systems, how to make LinkedIn work without hours of content creation or cringe, how to present yourself like the professional you are instead of underselling out of modesty. Once I could see those patterns clearly, I realised I could distil that repeatable value into something more accessible—a self-paced guide that gave people the blueprint without requiring my time on every call. It's not a replacement for the 1:1 (those are still there for people who want deeper, personalised work), but for £50, most producers can get what they need.

I know that some people might think: "You're a headhunter—shouldn't candidates talk to you for free?" And yes, absolutely—if I'm working on an open role or meeting producers to add to my network, those conversations cost nothing. They never have, they never will. But the Power Hours are different. They aren't recruitment calls; they are a type of career mentoring. And I have to prioritise my time somehow, especially when producers are asking for CV reviews, LinkedIn audits, and strategic advice that had nothing to do with a specific job. The paid sessions create a boundary that let me do that work properly, for people who genuinely want it, without burning out.

January: Discovering the Joy Factor

January also brought one of the year's most interesting recruitment challenges: an EP role at an international animation studio. On paper, it was the standard EP wishlist: someone who could manage day-to-day production, wrangle freelancers, drive business development, develop talent, and convert opportunities. The full package that many creative companies wants and few people can genuinely deliver.

But working with an animation company added a dimension I hadn't fully considered before: taste in animation is fundamentally different from taste in live-action production. The quality of this studio's work was exceptional—that's a given. But what does "taste" even mean ?

After speaking with dozens of candidates and really listening to how they talked about work, I landed on something that felt true: a sense of humour. Or if not humour exactly, then joy. Animation, even when it's sophisticated or dealing with serious subjects, has to have an element of play, of delight, of creative mischief. This puts it in a different emotional register than the moody, romantic, fashion-adjacent work that's trendy in high-end live-action production.

This realisation became my compass for the search. I looked for producers who lit up when they talked about projects, who understood timing and absurdity, who could recognise when something was funny-weird versus just weird. It worked—I found the perfect candidate. But it took ages.

Which brings me to something important about how I work: I'm not fast, and I'm not cheap. I know many recruiters measure success by time-to-hire (TTH), and I'm sure if I audited my own metrics, they'd skew longer than industry average. But I don't care, my actual agenda is different.

For Curious Connections, a good outcome isn't a quick placement. It's a placement that lasts. It's a candidate who thrives in their new role, a company that's genuinely thrilled with their hire six months down the line. An equally good outcome is walking away from a search because I can't find the right person—I'd rather back away than force a bad fit.

A bad outcome is placing someone who doesn't work out. That's what I'm optimising against, and it requires time. Time to really understand both the company culture and the candidate's working style, aspirations, and life context. Time to ensure the KPIs are clear and achievable. Time to do the emotional labour of hand-holding as people consider these massive life decisions.

This search tested all of it. Even when I knew we'd found the perfect person, there was still work to do: helping them think through the narrative of her career, understanding how this role built toward their long-term goals, ensuring the cultural fit was genuine and getting absolute clarity on salary and profit share structures.

This experience crystallised something for me: companies without clear KPIs for their roles are essentially asking recruiters to guess what success looks like. And when candidates can't see the concrete measures of success upfront, they can't honestly assess whether they can deliver. It wastes everyone's time. The companies I work with that have robust KPIs from the start—those are the ones where placements happen more smoothly and last longer.

February - Finding My Voice on LinkedIn

Running parallel to all of this was my evolving relationship with LinkedIn. I'd always been more comfortable on Instagram—it feels personal, visual, community-oriented. But as I spent more time in my Power Hours, telling producers to leverage LinkedIn, I found myself practising what I preached.

The platform started clicking for me. Not in a "here's my hot take on the industry" way, but in a genuinely useful way—commenting, direct messaging, building actual relationships.

The more I encouraged producers to use LinkedIn strategically, the more I did it myself. Self-fulfilling prophecy, productive feedback loop—whatever you call it, it worked.

March: The Leadership Crisis Nobody's Talking About

If January was about volume, February was about a specific, concerning signal: an unprecedented number of senior producers—department leads, Heads of Production, Managing Directors—getting in touch. Not because they wanted to leave their companies for greener pastures. Not because they were being pushed out. But because they needed help.

These weren't exploratory "what's out there?" conversations. These were genuine cries for help from people who'd reached the top of the production ladder and found it profoundly unsatisfying. The job itself was breaking them.

This felt significant. Everyone in production knows the grind of junior and mid-level roles. But leadership is supposed to be the reward, isn’t it? Better money, more autonomy, strategic influence. Except what I was hearing was: isolation, impossible expectations, constant firefighting, the weight of responsibility without the resources to deliver, the pressure of protecting your team while absorbing all the shit rolling downhill from anxious clients.

It made me think about how we assign blame in this industry. Junior producers blame senior producers. Producers blame EPs. EPs blame agencies. Agencies blame brands. Brands blame market conditions. Everyone's pointing at someone UP the food chain.

But the reality is that everyone is struggling a bit these days - the whole system is under pressure, Obviously, not everyone's struggling ethically or equally—there are still plenty of people extracting wealth and value in ways that harm others. But the general mood, across every level, seems to be: exhausted, anxious, just trying to make a living.

I don't have solutions for this. But I think acknowledging it matters. If you're frustrated with your Head of Production, take a moment to consider that their job might be genuinely soul-destroying right now. Empathy doesn't excuse poor leadership, but it does give you more information about what's actually happening.

April: The Search for "Creative Taste"

March brought three or four briefs that all circled around the same frustrating requirement: "We need a producer with great taste."

I completely understand what companies are asking for. The problem is figuring out how to assess it.

What clients actually mean is they need someone who can steer creative decisions in a particular direction. Someone whose frame of reference skews a certain way. Someone who intuitively understands a specific aesthetic or sensibility. That's real, and it matters.

The problem is finding it. You can't assess "taste" from a CV. You can't train an AI to recognise it. People's CVs are barely the best version of their experience, let alone windows into their aesthetic sensibility. And so much of what work you've been able to produce depends on luck—who you knew, what opportunities landed in your lap, which chips fell where.

The only way I've found to assess this is through conversation. Lots of conversations. Asking about cultural and artistic reference points, what they're watching and reading and listening to, what work they admire and why, what they think is overrated. Often, if they reference things I haven't heard of, that's actually a good sign—means they're digging deeper - that’s incredibly valuable.

But here's the admission: this means I have to constantly educate myself. I have to stay alert to what's happening in culture, not just in advertising. I have to watch the work, read the think pieces, understand the discourse. This is part of why I'm “slow”. You can't shortcut taste, and you can't automate it.

During this period, I was working on roles across the spectrum: one at a brand, two at production companies, one in-house at an agency. All of them needed this "creative steering" quality. All of them required me to go deep in conversations with candidates to find the people who could deliver it.

This takes time. This takes care. This is why AI won't replace good recruiters anytime soon.

May: The "Creative Producer" Problem

While we're on the subject of creative roles, I need to talk about a job title that's been driving me mad: "Creative Producer."

The term only makes sense if you're genuinely being hired to do both jobs—to be the creative and the producer, paid to deliver on both fronts. That's a real thing, and it's becoming more common. I placed two such roles at brands this year, and they were fascinating briefs because the companies genuinely needed someone who could ideate and execute.

But the vast majority of producers using this title aren't using it that way. They're using it as if it means they're somehow more than a regular producer. As if having creative instincts makes them a special type of producer.

I just don’t agree! Having a creative radar is implicit in being a producer. It's not a bonus skill—it's fundamental to the job. If you don't have that set of interests professionally, if you're not thinking about creative decisions and aesthetic direction, you're not a producer. You're a project manager. And that's fine! One isn't better than the other—they're just completely different jobs.

Every good producer is creative. The creativity just looks different. It's in problem-solving, in finding the elegant solution to a budget crisis, in knowing which HOD to pair with which brief, in understanding when to push back and when to facilitate. You don't need a special job title to claim that- you’re a producer.

June: Getting Kelly to Cannes

And then came the Kelly Gordon fundraiser. What started as an impulsive response to a LinkedIn post became one of the most meaningful projects of my year.

Kelly is brilliant—an entrepreneur who uses a wheelchair who has a lot to offer by being at Cannes Lions. She and business partner Emma Gardiner at With Not For put out a call for help; it was going to cost £6k to GKTC - that's almost double what it would cost a non Disabled person. When I saw it, my immediate thought was: "This should be easy. Six grand? The industry spends that without thinking. Every company going to Cannes is spending a minimum £5k per head. This is nothing."

I genuinely thought I'd reach out to a handful of companies that talk loudly about accessibility and inclusivity, and we'd have the money in a week. Maybe six companies doing £1k each. Done.

Oh my God, I was so wrong.

It became a massive amount of work. We spent two to three weeks where I was working until 10 pm every night. Emma, Kelly, and I became a proper team, and honestly, that was one of the best projects of my year. They're so professional, so clear about tone and politics and presentation. Coming from a production background where military precision is beaten into you, I'm usually impatient working with others who are more relaxed about details. But Emma and Kelly matched my energy completely—they understood how to communicate through social media, how to make designs that stand out, how to navigate the complicated politics of Disability advocacy without alienating potential supporters.

I was flying blind in many ways. I'm very much learning about disability access. But what I could do was check everything, ask questions, and not be afraid to say, "Is this okay? can I say it like that?” That felt like the most important learning: when you're working on DEI issues outside your lived experience, humility and asking questions isn't weakness—it's basic respect.

The money came in slowly. Five pounds. Ten pounds. Twenty pounds. Individuals, mostly. Not companies. Out of the £6,000 we raised, only two companies donated. Everything else was from individual people giving what they could. Isn't that amazing!

We hit the target literally five minutes before midnight on the final day of the fundraiser. And then we went to Cannes, and it was great. It's the start of something and watch this space to hear more about what Curious Connections and WNF have planned for all of those who donated and who want to push this conversation further.

But the experience also made me reflect on something uncomfortable: how easy it is to get angry about DEI issues, and how rarely that anger translates to action.

There was so much online commentary during this period—people blaming Cannes Lions, blaming the APA, the IPA, calling out companies, demanding statements. All very righteous. All very loud. And I found myself getting frustrated too, getting caught up in the blame game.

But Emma and Kelly didn't want that approach, and they were right. The blame is often misplaced. It's not Cannes Lions' fault that hotels in Cannes aren't accessible, that the Eurostar has access issues, or that event spaces weren't designed with wheelchair users in mind. This is way bigger than advertising, it's societal - it's got a name, "Disability Tax". The fundraiser actually helped spotlight these systemic problems in a constructive way. The goal wasn't to shame anyone—it was to get Kelly there and then work with the industry to ensure it's easier next year.

The angry call-out culture is mostly hot air unless you're willing to do that work every single day, all year long. I'm not here to be a trailblazer for social causes necessarily, but I do want to see more disabled people in production. We're missing out on incredible production talent because the industry has built systems that exclude people with disabilities. I'm not blind to the complications—the long hours, the reactive nature of the work, the intense deadline culture—none of that is naturally compatible with some disabilities. It's complicated, and it needs systemic change, and careful conversations, not just good intentions.

August-October: The American Contrast

Summer brought its usual slowdown, but autumn picked up with something unexpected: more work in New York. These roles are still ongoing, but they've taught me something important about the transatlantic divide in our industry.

The money, obviously, is the first shock. American producers make more $$ than their UK counterparts. But it's not just the money—it's the confidence, the optimism, the buoyancy of the market. American candidates certainly know their worth; some UK producers could learn a thing or to from them: they put on a show.

Too many UK candidates this year, when asked to complete a task as part of the interview process, sent over a quick email response. Maybe the content was fine, maybe they answered the brief, but the presentation was lazy. A Word document in size 12 Times New Roman font. A few sentences. Done.

This isn't good enough anymore. Producers need to see themselves as B2B marketers. Every interaction with a potential employer is a pitch. Every email, every task response, every CV is an opportunity to demonstrate your production skills—your ability to communicate clearly, to make things look polished, to think strategically about presentation.

We have the tools now. Canva, Gamma, Otter—there are so many ways to make your work look professional without spending hours on it. I'm not suggesting people use AI to generate ideas or content (please don't), but using tools to improve presentation and clarity? Absolutely.

When I compare the candidates who put in that extra effort to package their responses properly versus those who didn’t, the difference in outcomes is stark. The polished ones get the job. Every time.

This applies to everything: CVs, email signatures, LinkedIn Banners, pitch responses, and trial tasks. Production is about making things look good under pressure. Number 1 piece of advice for producers looking to make a move next year - make every interaction with potential hirers look the best. How you present yourself is the first signal you make that shows them how you’d present their projects.

End of Year: The Redundancy Wave

Moving into the back end of the year, redundancies hit the industry hard. Every week seemed to bring another round of layoffs, another production department restructured, another group of talented producers suddenly looking for work.

It's been brutal to watch. But here's what I've also seen: opportunity still exists. The work hasn't disappeared—it's just shifted. Brands are building in-house teams. Smaller production companies are picking up projects that used to go to the big shops. Freelance rates are actually holding steady in some sectors.

The catch? Producers need to hustle. They need to open their minds to roles they might not have considered before—going in-house, moving into content production, exploring adjacent industries. They need to upskill—understanding AI tools, getting comfortable with new production workflows, broadening their technical capabilities. And they need to think about other ways they can add value to this industry beyond just "I'm a great producer."

This is exactly why I created my free Job Hunt Survival Kit. Because when the market's this tight, you can't afford to have a mediocre CV or a half-finished LinkedIn profile or no clear narrative about what you bring to the table. The producers who are landing roles right now? They're the ones treating their job search like a production project—strategic, polished, relentless.

The opportunities are there. But they might look different to 2008, and so does your profile and value.

IN SUMMARY

Looking back at 2025, here’s the summary themes for me:

Value and pricing. The Power Hour sessions taught me that when you deliver real value, you need to charge accordingly. I care deeply about making support accessible, especially when money's tight across the industry, but underpricing doesn't serve anyone—it makes the work unsustainable and often makes people undervalue what they're getting.

The pace of quality work. I'm slow, and I'm completely okay with that. My time-to-hire might not impress other recruiters, but my placement longevity does. When you optimise for the right outcome rather than the fast outcome, everyone wins.

Taste is real but impossible to automate. You can't assess creative judgement from a CV. You can't train an AI to recognise it. Finding producers with the right aesthetic sensibility requires deep conversations about references, culture, and what work they actually care about. This is where human recruiters—good ones who actually give a shit—will always have an edge.

DEI requires action, not just anger. The Kelly Gordon fundraiser taught me that righteous anger on social media rarely translates to material support. What matters is showing up, doing the unglamorous work, asking questions, and building systems that actually increase access. The Disability Tax is real, and changing it requires more than LinkedIn posts.

The industry is struggling at every level. From junior producers to MDs, everyone's feeling the pressure right now. That doesn't excuse bad behaviour, but it does contextualise it. Empathy is a strategic asset, even when—especially when—people are driving you mad.

Presentation matters more than ever. In a competitive market, producers who treat their job search like a production project—polished, strategic, thoughtful—consistently outperform those who don't. The Americans have this figured out. UK producers need to learn from them.

Your CV is your first pitch. This realisation crystallised everything I'd learned from those Power Hour sessions. The CV and LinkedIn guide I created this year isn't revolutionary—it's just the accumulated wisdom from reviewing thousands of producer profiles and seeing exactly where people lose opportunities. The producers who implement even half of what's in there? They're the ones getting callbacks. It's not magic; it's just production skills applied to your own career presentation.

Partnership and community are everything. Whether it was working with Emma and Kelly on the Cannes fundraiser, conducting Power Hours with producers trying to level up their careers, or building relationships on LinkedIn—the best work happened in collaboration. We're all buggering through this together, and having allies is how we keep pushing.

As I move into 2025, I'm thinking about how to scale the parts of this work that energise me (the mentoring, the strategic hires that regenerate companies, the problem-solving). I want to continue pushing the industry toward more inclusive practices. I want to keep learning from both my UK and US networks about what good production leadership looks like.

And I want to keep working with companies who understand that good recruitment isn't about filling seats quickly—it's about building production teams that actually last. If you're a Head of Production, EP, or MD who's tired of the churn, who wants hires that work, who's willing to invest the time to do this properly—let's talk.

I'm careful, and thorough—because that's how you build things that last.